Monitoring progress on the UN Sustainable Development Goals requires a huge amount of data. Citizen science could help fill important data gaps, say IIASA researchers.

Citizen science holds major potential to contribute data for monitoring progress on the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), according to a new study published in Nature Sustainability. The paper, which grew out of a workshop held at IIASA from 3 to 5 October 2018, describes current examples of citizen science data being used for SDG monitoring, potential areas that citizen science projects could contribute, and provides a roadmap to increase the use of citizen science data in areas where more data is needed.

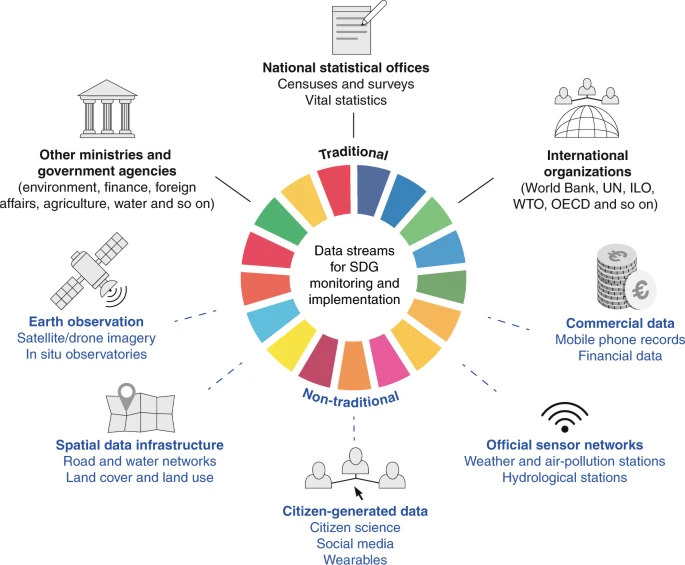

Tracking progress on the SDGs is a massive exercise in data collection and management. The 17 goals set by the UN in 2015 include 232 indicators. Of those, 88 require data that is not universally or regularly collected, and another 34 need data for which there is no international standard methodology for data collection. Even for the 104 indicators that do have regularly collected data, non-traditional data sources including citizen science could help increase the frequency or reduce costs.

“Citizen science is already contributing to a few SDG indicators, but there is potential for much more,” says IIASA researcher Linda See, a study coauthor. The new article involved a large community of citizen science experts from around the world, and was led by Steffen Fritz, who leads the IIASA Center for Earth Observation and Citizen Science.

For example, people around the world are contributing important data on biodiversity through long-running citizen science projects observing wildlife. The volunteer organization BirdLife provides international data on bird sightings that is used by official international organizations monitoring endangered species. On a national level, some countries are using citizen science as a way to increase data collection or to reduce costs: in the Philippines, for instance, citizen scientists are collecting household census data on poverty, nutrition, health, education, housing, and disaster risk, which is being used in the country’s official reporting to the UN.

One barrier to the use of citizen science data is a concern about data quality: How does data collected by volunteers stack up against official data sources collected by experts? In fact, research by IIASA scientists and others in the field has shown that through training, feedback, and other best practices, data gathered by non-experts can rival that collected by scientists, often at a much lower cost.

Particularly for the 34 SDG indicators where there is no standard international data source, the researchers see major potential for citizen science in closing the gaps. For example, one area with lacking data is marine debris, or ocean litter. Although the issue has gained great interest from the public, data collection currently relies mainly on visual observations by scientists, with no internationally agreed protocol. Citizen science projects to measure and record pollution are being incorporated to a growing extent in public projects to clean up beaches or waterways.

The researchers say that this involvement could bring benefits beyond just data.

“Through citizen science, people around the world could become much more involved not only in monitoring these indicators, but also in implementing the sustainable development agenda,” says Fritz.