Five years ago, Silicon Valley was rocked by a wave of “brogrammer” bad behavior, when overfunded, highly entitled, mostly white and male startup founders did things that were juvenile, out of line and just plain stupid. Most of these activities – such as putting pornography into PowerPoint slides – revolved around the explicit or implied devaluation and harassment of women and the assumption that heterosexual men’s privilege could or should define the workplace. The recent “memo” scandal out of Google shows how far we have yet to go.

It may be that more established and successful companies don’t make job applicants deal with “bikini shots” and “gangbang interviews.” But even the tech giants foster an environment where heteronormativity and male privilege is so rampant that an engineer could feel comfortable writing and distributing a screed that effectively harassed all of his women co-workers en masse.

This is a pity, because tech companies say they want to change this culture. This summer, I gave a talk at Google UK about my work as a historian of technology and gender. I thought my talk might help change people’s minds about women in computing, and might even help women and nonbinary folks working at Google now. Still, the irony was strong: I was visiting a multibillion-dollar tech company to talk about how women are undervalued in tech, for free.

Facing common fears

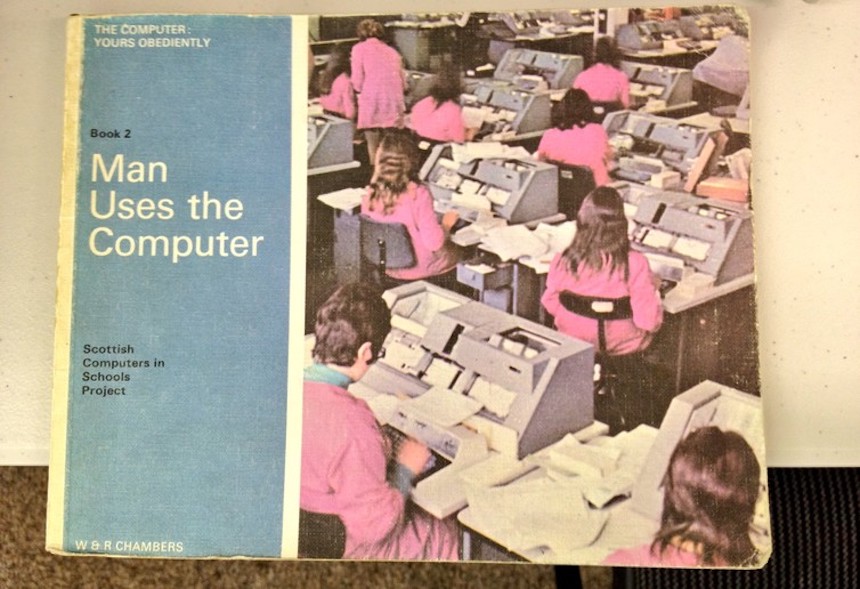

I went to Google UK with significant trepidation. I was going to talk about the subject of my upcoming book, “Programmed Inequality,” about how women got pushed out of computing in the U.K. In the 1940s through the early 1960s, most British computer workers were women, but over the course of the ’60’s and ’70’s their numbers dropped as women were subjected to intentional structural discrimination designed to push them out of the field. That didn’t just hurt the women, either – it torpedoed the once-promising British computing industry.

In the worst-case scenario, I imagined my talk would end with a question-and-answer period in which I would be asked to face exactly the points the Google manifesto made. It’s happened before – and not just to me – so I have years of practice dealing with harsh critics and tough audiences, both in the classroom and outside of it.

As a result of that experience, I know how to handle situations like that. But it’s more than just disheartening to have my work misunderstood. I have felt firsthand the damage the phenomenon called “stereotype threat” can wreak on women: Being assumed to be inferior can make a person not only feel inferior, but actually subconsciously do things that confirm their own supposed lesser worth. For instance, women students do measurably worse on math exams after reading articles that suggest women are ill-suited to study math. (A related phenomenon, impostor syndrome, runs rampant through academia.)

A surprising reaction

As it happened, the audience was familiar with, and interested in, my work. I was impressed and delighted with the caliber and thoughtfulness of the questions I got. But one question stood out. It seemed like the perfect example of how the culture of the tech industry is so badly broken today that it destroys or significantly hinders much of its talent pool, inflicting stereotype threat on them in large numbers.

A Google engineer asked if I thought that women’s biological differences made them innately less likely to be good engineers. I replied in the negative, firmly stating that this kind of pseudoscientific evolutional psychology has been proven incorrect at every turn by history, and that biological determinism was a dangerous cudgel that had been used to deprive black people, women and many others of their civil rights – and even their lives – for centuries.

The engineer posing this question was a woman. She said she felt she was unusual because she thought she had less emotional intelligence and more intellectual intelligence than most other women, and those abilities let her do her job better. She wondered if most women were doomed to fail. She spoke with the uncertainty of someone who has been told repeatedly that “normal” women aren’t supposed to do what she does, or be who she is.

I tried to empathize with her, and to make my answer firm but not dismissive. This is how structural discrimination works: It seeps into all of us, and we are barely conscious of it. If we do not constantly guard ourselves against its insidious effects – if we do not have the tools to do so, the courage to speak out, and the ability to understand when it is explained to us – it can turn us into ever worse versions of ourselves. We can become the versions that the negative stereotypes expect. But the bigger problem is that it doesn’t end at the level of the individual.

A problem of structure

These misapprehensions bleed into every aspect of our institutions, which then in turn nurture and (often unwittingly) propagate them further. That was what happened when the Google manifesto emerged, and in the media frenzy that followed.

That the manifesto was taken as a potentially interesting or illustrative opinion says something not just about Silicon Valley, but about the political moment in which we find ourselves. The media is complicit too: Some media treated it as noteworthy only for its shock value. And others, rather than identifying the screed as an example of the writer’s misogyny, lack of historical understanding, and indeed – as some computer professionals have pointed out – lack of understanding of the field of engineering, handled the document as a think piece deserving consideration and discussion.

The many people who said openly and loudly that it was nothing of the sort are to be commended. But the fact that they had to waste time even addressing it shows how much damage casual, unreflective sexism and misogyny do to every aspect of our society and our economy.

The corporate response

Google, for its part, has now fired the writer, an expected move after the bad publicity he has helped rain down on the company. But Google has also – and in the very same week that I gave my talk there – refused to comply with a U.S. Department of Justice order to provide statistics on how it paid its women workers in comparison to men. The company claims that it might cost an estimated US$100,000 to compile that data, and complains that it’s too high a cost for their multibillion dollar corporation to bear.

The company will not expend a pittance – especially in relation to its earnings – to work to correct allegedly egregious gender-biased salary disparities. Is it any surprise that some of its employees – both men and women – view women’s contributions, and their very identities, as being somehow less inherently valuable or well suited to tech? Or that many more silently believe it, almost in spite of themselves?

![]() People take cues from our institutions. Our governments, corporations, universities and news media shape our understandings and expectations of ourselves in ways we can only partially understand without intense and sustained self-reflection. For the U.K. in the 20th century, that collective, institutional self-awareness came far too late to save its tech sector. Let’s hope the U.S. in the 21st century learns something from that history. At a time when technology and governance are increasingly converging to define who we are as a nation, we are living through a perfect – if terrifying – teachable moment.

People take cues from our institutions. Our governments, corporations, universities and news media shape our understandings and expectations of ourselves in ways we can only partially understand without intense and sustained self-reflection. For the U.K. in the 20th century, that collective, institutional self-awareness came far too late to save its tech sector. Let’s hope the U.S. in the 21st century learns something from that history. At a time when technology and governance are increasingly converging to define who we are as a nation, we are living through a perfect – if terrifying – teachable moment.

Marie Hicks, Assistant Professor of History, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.