The House is focused on important risks from the sale of Americans’ data, but legislators can pursue more comprehensive data brokerage measures.

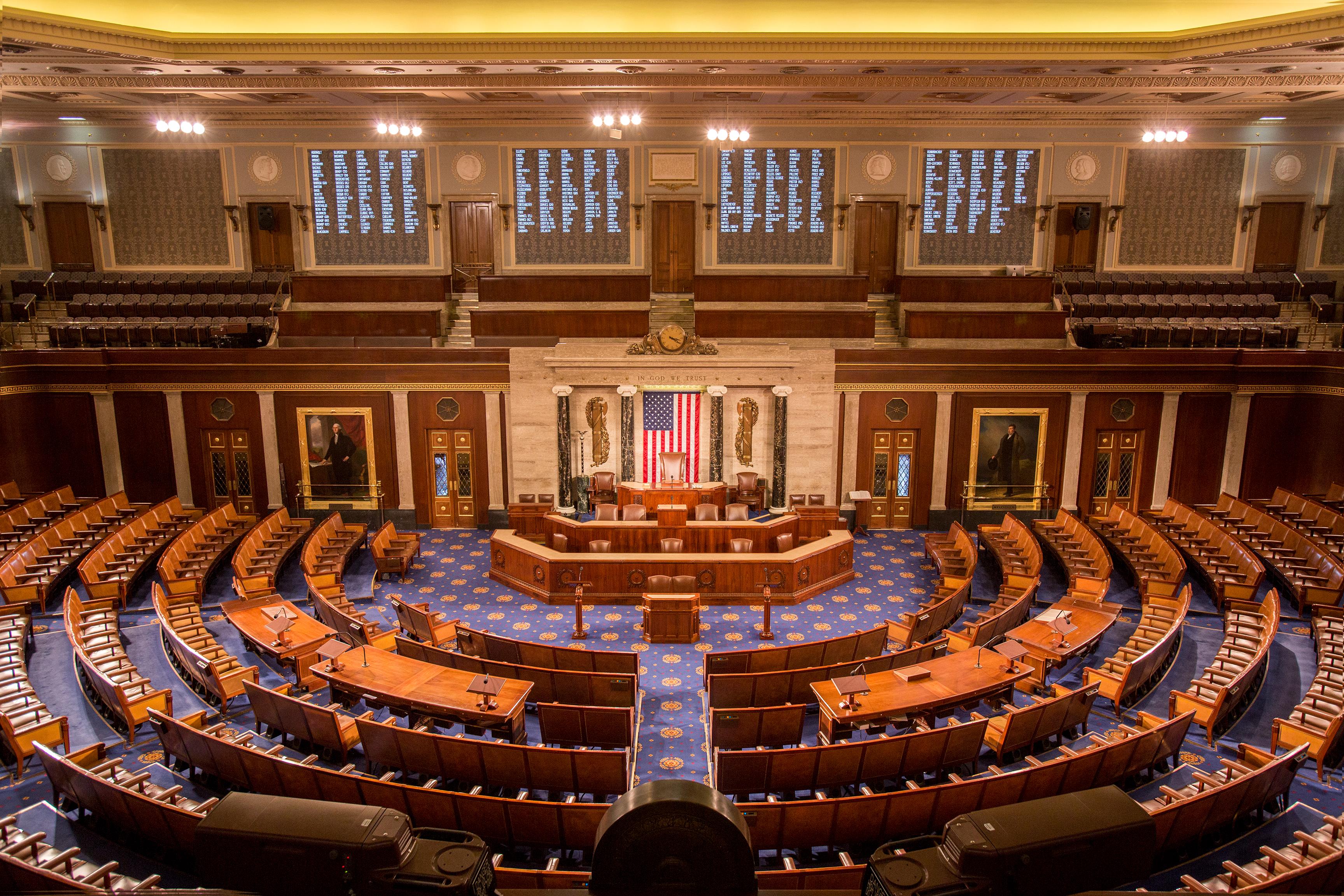

On March 20, the House voted 414-0 to pass the Protecting Americans’ Data from Foreign Adversaries Act. The bill seeks to limit the data that U.S. data brokers could sell about U.S. persons to individuals located in North Korea, China, Russia, or Iran—and to entities headquartered, owned by a person, or otherwise controlled by the governments in those countries. The measure was introduced just a few weeks ago, alongside a TikTok and foreign-owned app divestment bill, and now heads to the Senate for consideration.

The central concern behind the bill stems from the highly unregulated U.S. data brokerage industry, composed of thousands of companies in the business of collecting, packaging, and selling data, including identified or easily identifiable data about individuals. Members of Congress in both parties as well as the intelligence community have expressed worries that foreign adversaries could use this ecosystem to obtain data on U.S. government employees, clearance-holding contractors, military service members, and other individuals to profile, blackmail, coerce, or target them. The bill also comes on the heels of an executive order designed largely to place limits on U.S. data brokers’ sale of certain sensitive data to certain foreign actors. The House Energy and Commerce Committee has demonstrated strong bipartisan leadership in drawing attention to these problems.

It is important to not make the perfect the enemy of the good—and typically, any marginal improvement on the status quo when it comes to data brokerage would benefit consumer privacy and national security. There are several elements of the bill that are noteworthy in this respect, including the fact that its protections are aimed beyond government personnel, it would not carve out sales of covered data below a certain threshold (for example, data set size), and it has a fairly strong definition of sensitive data that it could put into federal law. At the same time, given the ongoing executive order process on bulk data transfers and national security, it is difficult to make sense of the reasoning behind this new bill and why Congress is taking such a weak approach.

The bill purports to tackle a problem similar to what the executive order is already addressing under existing law—except by creating a new law, and with an ultimately narrower scope, fewer measures to counteract circumventions, a different and non-national security-focused enforcement agency in charge, and a significantly slower timeline for identifying and mitigating national security risks. If Congress is going to spend time writing a new law focused on the data brokerage ecosystem, it should aim bigger and look beyond a national security framework to avoid coming away with a narrower and weaker enforcement regime, with less benefit to national security, than the executive branch can build under current law. The bill’s drafters are focused on important data brokerage problems, and they should be commended for injecting data brokerage into the too narrowly focused policy conversation dominated by debates about TikTok and non-U.S. apps. But the Senate should force a significant amendment and strengthening of the bill before pushing it forward and trying to address the privacy and security risks the House has highlighted.

Unpacking H.R. 7520’s Definitions

The House bill is in some ways broader than the administration’s executive order. It focuses on national security risks from the brokerage of all Americans’ data, not just data on government-linked individuals (a constraint the executive branch has that Congress does not), and it does not have minimum thresholds for what counts as a covered data sale. The bill’s description of sensitive data builds on a previous comprehensive privacy bill (discussed more below)—a possible argument alone for getting the bill into law. But the bill completely excludes from its scope the many first-party collectors of data that also sell it and, in doing so, carves out a significant part of the data brokerage industry and a large driver of the market for geolocation data: mobile apps. The bill does not contain language to address the risks of data purchases routed through third countries, either. All told, if the executive branch can draft regulations under current law that address risks from both first- and third-party data collectors selling data, with some attempt to address a piece of the third-country circumvention problem, it is confusing why Congress is pushing a new law that is weaker and ultimately narrower, focused only on third-party data brokers.

Covering the sale of data about any U.S. individual to the listed countries, not just (as the executive order focuses on) data about defined categories of national security personnel—such as U.S. government contractors, active-duty U.S. military personnel, and current and recent, former senior U.S. government employees—is an important choice. The bill defines U.S. individuals as any natural persons residing in the United States. This is a stronger approach to the sale of Americans’ data because it includes more people under its protections. In fact, it’s many multiples more, if you count the more than 2 million people serving in the military (active duty and reserve), the estimated 3 million or so people with security clearances, and so on against the 336 million-plus people living in the country.

It is also a stronger approach because attempting to limit the sale of data about individuals, organizations, or even places through a list-based framework is inherently limited. Malicious actors will most likely figure out ways around it, and in a foreign intelligence context, they can dance around the letter of the law to access data on family members, close acquaintances, and others who lie just outside the scope of regulatory coverage. This is one area where the White House, the Justice Department, and the Department of Homeland Security face legal constraints in the recent executive order, and its underlying authority (the International Emergency Economic Powers Act), and therefore have to rely on a list-based approach that draws out national security risks. It’s much like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) taking a list-based approach to prohibiting the sale of data on defined “sensitive locations”—it is an efficient, clearly understandable way for an executive branch agency to mitigate harm in the interim but fundamentally requires new federal laws to tackle the problem.

The bill does not have minimum thresholds for data set sizes; in other words, any covered third-party data broker engaging in the data sales laid out in the bill would be subject to regulation, whether it sold data on a single U.S. individual or on 2 million. Such a design is different from the executive order’s language, which scopes data brokerage regulations around “bulk transfer” of sensitive personal data and transfers of any size or amount of covered, government-related data. For instance, the proposed regulations following the executive order could potentially cover only the transfer of more than 100 U.S. persons’ biometric data on the low end or only the transfer of more than 1,000 U.S. persons’ biometric data on the high end. The bill drops this threshold limitation.

That said, a serious gap in the bill is that it would only prohibit third-party data brokers from selling certain sensitive data, which is not the case for the executive order. (The scope of covered data is discussed next.) This is because the bill defines a data broker as

an entity that, for valuable consideration, sells, licenses, rents, trades, transfers, releases, discloses, provides access to, or otherwise makes available data of United States individuals, that the entity did not collect directly from such individuals, to another entity that is not acting as a service provider.

Some state laws, such as data broker registry laws in California, Vermont, Texas, and Oregon, define data brokers (generally) as companies selling data on individuals with whom they have no direct business relationship. Put simply, they define covered data brokers as third parties that are not selling data on their own customers and users. While many data brokers fall under the third-party category, there are also many first-party data collectors—from online health services to retailers to mobile apps—that sell their own customers’ and users’ data. For example, much of the booming market for people’s geolocation data—historical data, real-time data, pattern data, and more—is driven by mobile apps that quietly sell their users’ GPS and location data to other organizations. Not covering first-party sale of data means the bill would fail to cover a substantial portion of data brokerage activity. It also means, in a national security context, that mobile apps, pharmacies, retailers, telehealth services, and social media platforms could sell sensitive data types on military and government users to foreign governments with no restriction.

And here’s the real irony of this situation: If the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (the TikTok divestment bill) became law, and this data broker bill became law as well, TikTok could still legally sell Americans’ data to the Chinese government—whether it was owned by ByteDance or not.

Additionally significant is the bill’s definition of “sensitive data.” The term includes government-issued identifiers (for example, Social Security Number, passport number); information revealing past, present, or future health conditions or treatments; financial account, credit card, and income numbers; biometric information; genetic information; “precise” geolocation information; and some other data types fairly common to sensitive data lists in bills and regulations. Many of these categories are similar to the categories laid out in the recent executive order on bulk data transfer, such as genomic data, biometric data, and precise geolocation data. The bill also contains fairly strong language to cover data used to infer the listed data types.

However, the bill notably diverges from many of these other bills, regulations, and proposals by including under the scope of sensitive data:

(G) An individual’s private communications such as voicemails, emails, texts, direct messages, mail, voice communications, and video communications, or information identifying the parties to such communications or pertaining to the transmission of such communications, including telephone numbers called, telephone numbers from which calls were placed, the time calls were made, call duration, and location information of the parties to the call. …

(J) Calendar information, address book information, phone or text logs, photos, audio recordings, or videos, maintained for private use by an individual, regardless of whether such information is stored on the individual’s device or is accessible from that device and is backed up in a separate location.

(K) A photograph, film, video recording, or other similar medium that shows the naked or undergarment-clad private area of an individual.

This is where it becomes clear that the bill drew its definition of “sensitive data” from the American Data Privacy and Protection Act, the comprehensive privacy bill from the last Congress, and added in one more line covering “information that reveals the status of an individual as a member of the Armed Forces.” The definitions are almost identical.

Of course, the sale of private communications, calendars and related information, and naked photos and videos, if that were to occur, would certainly pose national security risks. A foreign actor could exploit access to Americans’ private communications in a variety of ways, including to identify financial hardship, marital problems, or any other piece of information that could be used to approach or blackmail an individual to spy. On first glance, the inclusion of this kind of information could raise interesting questions about speech and the transmission of content. The bill addresses this head on by clearly stating that a “data broker” does not include an entity “transmitting data, including communications of a United States individual at the rest or direction of such individual”; an entity “reporting, publishing, or otherwise making available news or information that is available to the general public”; or an entity “acting as a service provider.” This would appear to address concerns about communications. Putting all of these considerations together, there could be an argument, despite the bill’s many drawbacks, that it would be valuable for the U.S. to get this “sensitive data” definition passed into federal law.

The bill also limits data sales to entities “controlled by a foreign adversary” in China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea (drawing the country list from 10 U.S.C. § 4872). An entity is defined as “controlled by a foreign adversary” if the entity or at least 20 percent of its owners are domiciled, headquartered, principally operating, or legally organized in a foreign country on the list; or if the entity is a person “subject to the direction or control of a foreign person or entity” domiciled, headquartered, principally operating, or legally organized in a foreign country on the list. Interestingly, this language does not explicitly call out potential buyers’ connections to foreign governments or intelligence services per se but, instead, orients the national security concerns around where individuals and organizations are based, ostensibly due to concern about authoritarian governments’ intelligence laws and extralegal coercive measures. As for the four countries: They are well familiar to anyone reading national security documents, such as the U.S. intelligence community’s annual worldwide threat assessment. The bill’s list is slightly shorter than the one the Commerce Department developed in response to Executive Order 13873 from 2019, which includes China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea as well as Cuba and Venezuela.

Significantly, the bill does not make any mention of third countries, or cases where, for instance, a Chinese intelligence agency could use an intermediary shell company in Europe to acquire data. This has been a criticism of the executive order—that it will not stop all sales. While this idea of eliminating risk completely is a false bar for the executive order or other national security policies, there is a greater reason why the executive branch faces constraints in tackling those activities; it has to draw on existing laws and authorities. Congress, however, does not. The stated national security concerns about data brokerage again lead to the question of why the bill does not aim to do more through new law.

Limits to the Bill’s Enforcement Regime

The way the bill would be enforced—and, thus, deliver the purported protections that would be afforded to Americans’ data and national security—is quite limited. On top of the exclusion of first-party data brokers and other limits covered in the preceding section, the enforcement regime proposed by the bill is substantially weakened by giving the FTC not broad privacy authority, but a national security-focused data authority. The FTC is deeply expert on data privacy but is not set up, institutionally or in knowledge, to deal with fast-moving national security issues; one can count on a single hand the number of FTC employees with high security clearances, and the standard of multiyear case timelines is unworkable in a fast-paced national security context. These limits in enforcement approach again point back to the need for Congress to pass a broader bill regulating data brokerage generally—and to give the FTC more authorities in that vein.

Under the bill, any violation of the data sale prohibitions by a third-party data broker would be considered an “unfair or deceptive act or practice” under Section 5 of the FTC Act. This would give the FTC the power to investigate and bring enforcement actions against violators, as it already does for companies violating the FTC Act currently with respect to facial recognition abuses, deceptive privacy statements, or breaches of consumer health data. If the bill was broadly about consumer privacy and investigating company data practices, this assignment of authority would make total sense and fit in with work the FTC is already doing. When it comes to a national security context, however, the reasoning is less sound.

Make no mistake: The FTC is doing important, leading work to address data brokerage and risks to consumers’ privacy. But the FTC’s primary expertise areas surround consumer protection, privacy, and antitrust rather than national security and foreign governments’ intelligence operations. If Congress is going to give the FTC new authorities around data brokerage, it should give the commission authorities to protect all consumers against all kinds of privacy risks, not just against selected activities defined to impact national security. Congress’s concern should be how all individuals in the U.S. are impacted by the data brokerage industry, spanning everything from counterintelligence risks to ongoing harms of stalking and gendered violence, threats to judges and elected officials, scams of elderly people suffering from Alzheimer’s, and predatory targeting of people seeking medical care. The legislature alone has the power to put those kinds of comprehensive reforms in place.

And even if Congress did want additional provisions in law focused specifically on data brokerage and national security, the FTC is not set up to systematically ingest classified intelligence and assess national security issues across the organization, such as the ways in which Chinese or Russian intelligence agencies covertly obtain data about U.S. persons to blackmail targets, build dossiers on selected individuals, or otherwise run intelligence operations. As of October 2022, according to a congressional letter, just four people at the FTC had high-level (Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information, or TS/SCI) security clearances. Foreign governments could therefore buy Americans’ sensitive data through intermediaries or use proxy groups or front companies to acquire data, and the FTC would not be as well equipped as some other agencies to track and access the intelligence needed to detect those activities. The House bill’s choice of enforcement organization for a national security scope would greatly undermine its effectiveness.

It is a continual problem that Congress has a stream of bills seeking to give the FTC more authority to protect against data privacy abuses (a positive step) but without enough conversation on the Hill about giving the FTC any additional resources for its privacy team to scale up enforcement. The FTC has for years had approximately 40 attorneys in its privacy division working to protect hundreds of millions of people—a testament to the attorneys’ expertise and incredible case output and a repeating signal of the legislature’s failure on increasing funding. Many of the offices and staffers supporting the House’s data broker bill have spent years working on privacy and well understand this point; many of them, in fact, are in the small group in Congress calling over and over to direct more funding to the FTC. Yet, it is worth stating this problem nonetheless, because it impacts the national security issues discussed above and the FTC’s ability to substantially invest in hiring security-cleared people to work on cases.

This comes back to the need to give the FTC wider privacy authorities not heavily dependent on understanding foreign governments’ data-gathering activities, intelligence objectives, and secret networks of proxy groups and front companies. The prime example of those wider authorities would be heavily restricting or outright banning the sale of U.S. persons’ sensitive data to any organization, foreign or domestic—because the FTC could investigate and enforce against data sales themselves without needing access to sensitive intelligence about foreign governments.

Another reason for wider legal reform is that FTC cases on data privacy and cybersecurity abuses take years. This is already too long in a consumer protection context—another reason for Congress to give the FTC and its prolific attorneys more funding and empower them to move faster—but is especially too long in a national security context. If a foreign intelligence agency is buying location and financial data on U.S. military bases to inform recruitment of spies in the military, the U.S. government cannot afford to wait years to merely find out a U.S. company is part of the transaction. Every day that goes by could mean more information exposed or more individuals profiled and targeted. The timeline for identifying and mitigating risks needs to be far quicker. This again begs the question of why the bill is constructed in such a fashion; if Congress is creating new legal authorities to address risks associated with data brokerage, it should heavily regulate all sales of data on Americans and give the FTC greatly enhanced powers to protect all people. Should Congress specifically wish to pursue measures to additionally address national security risks, the law it writes should not create a slower process than the one the executive branch is already building.

Legislators with the power to protect all Americans’ privacy from this ecosystem should use it—and doing so will ultimately improve protections for national security as well.

H.R. 7520, Off to the Senate

The Senate will now consider the legislation. It is again commendable that the House Energy and Commerce Committee has done much work on data privacy legislation and has drawn attention to the risks posed by data brokerage to Americans’ privacy and safety as well as U.S. national security. The sponsors are right to focus on this problem and what kinds of privacy measures can be implemented in the absence of a comprehensive federal privacy law.

Nonetheless, Congress is looking to pass a law that would seemingly hardly do more (if at all) than the executive branch is already able to do under existing law—which, given the extraordinary lack of U.S. data privacy and cybersecurity laws, is telling about the weakness and narrowness of the bill’s scope. Prohibiting the sale of data about lists of people or locations is a fine approach in the interim for the executive branch but a doomed-to-fail approach for legislators. As mentioned above, foreign governments could continue targeting people in the national security community through commercial data by just widening the net on individuals in the targets’ networks, outside the scope of the law. The failure to include any provisions about data sales to third countries further underscores the gaps in the bill’s narrow approach to data privacy and security regulation. It is important to recognize partial measures for what they are, particularly when the need for meaningfully new legislation is so great.

The best step for the Senate is to propose considerable amendments to the bill. Ideally, this would include designing restrictions on the sale of data to protect all Americans, especially individuals constantly impacted by stalking and gendered violence, not just those whose data is sold to certain foreign entities. For instance, Congress could consider banning the sale of Americans’ geolocation data and biometric data. Any Senate revisions to the bill should also come with discussion of greatly increased funding for the FTC, which has undertaken years of strongly bipartisan work on data privacy and cybersecurity enforcement—and desperately needs the resources to increase its impact. And if the bill does carve out any narrow areas of data sales, it should impose strong requirements on companies to implement comprehensive privacy, security, and compliance control programs for how data is gathered, aggregated, analyzed, stored, sold, and ultimately used, which can then be assessed by independent, third-party auditors and regulators.

If the Senate did choose to stick with the national security lens (which is again not preferable to comprehensive protections), then it needs to do substantially more than is happening under current law and executive authority. To accomplish this, the bill should drop the complete exclusion of first-party data brokers, add additional requirements into law for data brokers to track and vet their customers in all countries, require regular reporting from the covered companies to executive branch regulatory agencies, and ensure there is a way for both privacy experts and national security experts—who can access sensitive intelligence on foreign governments’ data-gathering activities—to make the enforcement regime effective.

There are at least two obvious counterarguments that could be raised. One is that executive orders come and go, and there is no guarantee that a future administration, regardless of political party, keeps the current executive order and attached regulations in place. It is of course true that executive orders do not have the staying power of a federal law. But this does not negate the point that Congress should pass a robust law, even if just a robust federal law focused on data brokerage (and leaving comprehensive privacy legislation writ large to a full package). Executive action potentially changing on a dime and the public needing comprehensive federal laws to protect against data harms are not mutually exclusive. The second, obvious counterargument that could be raised to this article is that Congress needs to pass what is “politically feasible” and that excluding first-party sellers of data from coverage—from mobile apps to major telehealth platforms—is the easiest path to passage. Yet this appears contradictory to Congress’s ability and responsibility to protect constituents from harm—because members should not be simultaneously stating that they believe there are considerable national security risks posed by the sale of Americans’ data, so much so that this bill is receiving attention and follow-through over many other policy issues, and that they also are willing to exempt and not push back against a considerable portion of the data brokerage market selling that very data.

While the current bill draws attention to an important issue—and its coverage of all Americans, fairly strong definition of sensitive data, and lack of a minimum data set threshold limitation are all positives—it has much further to go to make an impact.

– Justin Sherman is a contributing editor at Lawfare. He is also the founder and CEO of Global Cyber Strategies, a Washington, DC-based research and advisory firm. Published courtesy of Lawfare.